Show and Tell Day

Hello, all. I hope you are having a good Sunday.

Originally, I was going to use this day for a different editorial. Upon reflection, though, the topic of that post was premature. Maybe sometime I’ll revise and publish it, but for now, it feels unnecessary.

Since that left a hole in my schedule, I figured now was a good time to acknowledge a place where I’ve failed to provide vital nuance: my application of the adage, “Show Don’t Tell.” This is a writing rule that is heavily emphasized, and with good reason, but it’s not an absolute. There is a time and a place for Telling over Showing. I feel it’s important that we all understand where the line is and why. I’d also like to provide a recent example (one that will be explored more in a future review) where Telling really would be adequate to solve a book’s problems.

WHAT IS “SHOW DON’T TELL”?

Show Don’t Tell is writing advice that is at its purest form in storytelling with a visual component (movies, TV, games, plays, comics, etc.). The idea is that, when you can literally show important details to the audience, it is better to do so, rather than forcing information unnaturally into narration or dialogue. Examples of this include having dedicated scenes to demonstrate plot elements or character traits, using background details to visually showcase worldbuilding elements, and designing wardrobes / costumes / makeup / character models to communicate ideas through visual symbolism and exaggerated details.

I’ve seen detractors of Show Don’t Tell point out that literature is all Telling, with the implication being (as I understand it) that there is no practical difference between Showing and Telling in this medium. I heartily disagree with this. Just because things cannot literally be shown to the audience in a visual format, that doesn’t mean they can’t still be demonstrated. If anything, if the entire medium is technically telling the audience things instead of showing them, then going above and beyond to achieve the same effect is all the more important.

And this is where the true heart of Show Don’t Tell resides.

Time is a Precious Resource

The amount of information that can be conveyed within any story is limited.

Vanishingly few stories are told in real time. Outside of extremely short stories, it is far more common to see several hours, days, or even years compressed into a form that can be shared with audiences in minutes or hours. The only significant exception I can think of was 24, and that’s an exception that proves the rule: the whole gimmick of the show is real-time storytelling to up the tension within an action thriller. However, even acknowledging that 24 is an exception, it’s important to point out that it was still limited. Every commercial break was time that the narrative could utilize.

This is before we consider stories with multiple POVs. Even if you could get a close approximation to real-time storytelling, the moment the story needs to bounce between disparate locations, information needs to be cut. Again, I believe A House of Dynamite is an exception to this (though I haven’t seen the film itself), but as I understand it, this is another exception that proves the rule: each POV is meant to showcase the same time interval from different perspectives, meaning that the movie has to be longer than the span of time it actually portrays in order to achieve this effect.

The vast majority of the time, a writer must make hard choices. If literally everything were shared with the audience, then the story would lose out on pacing and narrative flow. It would become a bloated mess. Things need to be cut.

What the writer is left with after the cuts are made are:

Story elements (plot, characters, worldbuilding) that appear within scenes and play out before the audience. This is Showing.

Story elements that are exposited to catch the audience up without needing the play things out. This is Telling.

WHEN AND WHY TO SHOW OR TELL

Showing

Showing should be applied to things that are … important to the story.

I realize how unhelpfully vague that is, but it really is that simple.

Most of the time, Show Don’t Tell is not a conscious decision. Without Showing, there is no story. Every scene, by its very nature, Shows the audience something. Without scenes to string together (or, for stories that are one scene, without the events that take place within that scene), then what one would be left with wouldn’t really be story. It would be a concept or outline.

It’s when one moves to the periphery of the narrative - to backstories, events the support that core plot, character traits, and so on - that things start to get tricky. Does the audience really need to see a conversation that exists solely to establish a specific character trait? Do we need an entire scene to show an inciting incident in a detective story? Can’t the limits of a magic system be exposited instead of painstakingly demonstrating the mechanics?

And the problem is, this needs to be judged on a case-by-case basis. Not every element in every story can be judged by the same metrics, because even in stories that share elements, those elements are not going to be used the same way every single time.

Still, I promised clarification, so this is the metric I use to judge whether something needs to be Shown:

Is this important to the audience experience?

Which can be further broken down into three questions:

1. For whole scenes, if the scene can be accommodated in the story without throwing off the pacing, will the audience get more out of the story if they are able to experience events with the characters rather than learning of these events via exposition?

2. For details about the world (barring historical events), is it important for the audience to remember this, or can they simply tune it out to a general background vibe?

3. Is this element meant to be a load-bearing pillar for either an emotional narrative beat or a thematic element?

And to explain what I mean by this, I have two examples.

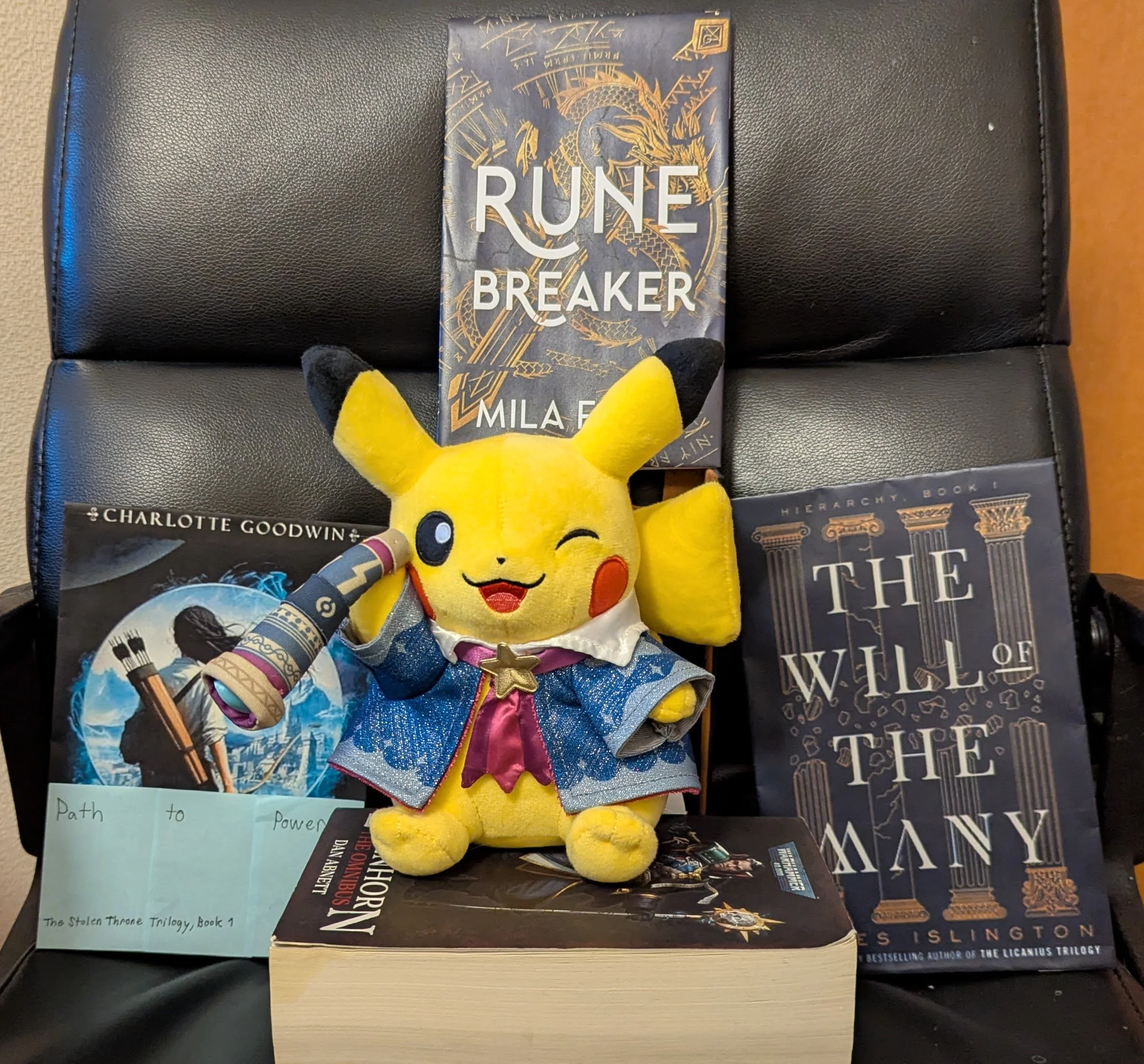

Questions 1 & 3: The Queen of Vorn / Path to Power

Yeah, I need to unearth this book again. Sorry about this. It really is the best example of these two questions out of any book reviewed on this site thus far.

The reason why I argued that both versions of that book were so imbalanced in terms of Show vs. Tell is because there were multiple points where the answer to Sub-Questions 1 & 3 was a definitive “yes”, yet the audience was simply Told about them. To name just three examples:

Emma’s abduction, which could have made for a harrowing chapter full of tension and emotional depth, is played as a video. Not only does playing the video feel incredibly contrived in-context, but this is effectively Telling, as the events are being replayed after the fact for a character who is not watching the video for any reason linked to plot or character. We aren’t experiencing the events of the abduction - we’re experiencing the reaction of a bored, bitter officer brooding over how she flushed her career down the toilet. That might have been fine if the story was about said officer’s career, but it’s not. It’s about the abduction and its consequences for Emma.

Emma’s reaction to learning the truth of her origins is handwaved, with the story cutting to Tom and Emma deciding whether to go to Dunia. This should have been a moment of immense emotional upheaval for Emma. There was such rich opportunity for character drama. Instead, it is brushed aside so quickly that Emma might as well have known the truth all along and been waiting in exiile for someone to summon her home.

In Path to Power, scenes of the goblin genocide that were previously Shown via Lila and Grinthy’s POVs in The Queen of Vorn are converted into more videos for a less bored, less bitter officer to watch and casually comment upon with her coworker. This is not adequate when the thematic argument that drives the whole plot is “genocide is bad.”

One of the few elements of the book that did work well was the evolving dynamic between Tom and Garrad - because the author Showed it to us. We got multiple scenes of the pair being antagonistic before circumstances allowed Tom to prove himself to Garrad. We got to experience important interactions that were allowed for by the pacing of the story, and these interactions laid the emotional foundation for a satisfying conclusion.

Question 2: Hierarchy Quartet

In The Will of the Many and The Strengh of the Few, the rules of the magic system grow increasingly more important as the story continues, Vis is initially unable to use Will, so the audience only really needed to understand enough to grasp the threats he was confronted with when facing people who could. Once he does gain the ability to use Will, though, it became important to understand how it could be applied to solve problems, so that we could truly appreciate the level of challenge Vis faced at any moment.

Islington was proactive about this. Early in The Will of the Many, we get a scene of Vis fighting in an underground tournament against someone enhanced by Will, practically demonstrating how much of a difference even a small amount of ceded power can make. This is followed up by more scenes to demonstrate things like Transvects and the the power wielded by people even higher up on the pyramids. Once Vis gained access to Will in The Strength of the Few, there were multiple scenes of Vis learning to use specific techniques or applying them to minor challenges.

Could Islington have just exposited about what Will can do? Possibly. Some of what Vis learns to do in The Strength of the Few retreads information that was Told to us in The Will of the Many. However, practical demonstrations both made the rules of the magic system more memorable and firmly established what Vis is or isn't capable of doing with that power when faced with problems.

Telling

Telling sits in a gray area. Usually, if information is Told to an audience, it should be important enough for us to know. Otherwise, the time used to Tell us things could be put to more productive purposes. However, Told information usually doesn’t need reinforcement through practical demonstration.

Telling can be used to:

Handwave scenes that, while important within the overall chronology of the story,

Establish worldbuilding mechanics that add to the overall flavor of the world without being important to driving the story forward.

Introduce other important details that aren’t load-bearing pillars for emotional moments or thematic elements of the story.

In The Queen of Vorn, the revenge motive that drives Lila’s genocide of the goblins was Told to us. I criticized this at the time because the point just kept getting hammered upon within Lila’s POV, as if we were expected to feel some emotional investment in her because of it. Telling fell short of the mark there because Showing, via a flashback or some other narrative device, would have better suited that objective. This problem is corrected in Path to Power. Lila is no longer a POV character, so her revenge motive in mentioned in passing by the Zargons. That works perfectly well. In that version of the story, we aren’t being asked to feel any emotional investment - it’s just a handwaved explanation for why Lila is doing what she’s doing. Telling is the better path to take in that circumstance.

In The Will of the Many, we are Told the numbers of the standard Hierarchy pyramid of Will. Outside of a single moment where a question is asked about the Catenan Republic’s population math not working (which appears to have been answered in The Strength of the Few), these numbers do not matter. They simply exist to give the audience a sense of power scaling between tiers. The precise number of people that separates, say, a Quartus from a Quintus never truly matters, even once we get into The Strength of the Few and Vis starts using Will. All that really matters to the narrative in such a matchup is that the Quartus has an overwhelming advantage in terms of raw power.

SOMETIMES, TELLING IS ENOUGH

I know that, even with this guidance, there’s still a lot of vagueness as to when Showing is best versus when Telling is enough. Like I said, it is a case-by-case basis. Writers need to really evaluate what’s essential to the narrative. Having beta-readers and editors who are willing to think this through and provide good feedback on what is or isn’t necessary to Show is important to overcoming this obstacle.

The focus should be on Showing first. Obviously, this isn’t always practical from a length or pacing perspective, but it’s important to demonstrate all of the most essential aspects of the narrative on the page. Telling should then be the fallback position to address length or pacing issues.

Many stories will likely see some back-and-forth as the writer experiments with Showing and Telling the same element. And, of course, you don’t need to Show literally everything in early drafts. Some things will be Told from the beginning of the process. What’s important is to make that decision deliberately, with Telling either being a placeholder or something that you have decided not to Show for practical, narrative reasons.

Aside from pacing, Telling does have one other vital usage: as a means of filling in the cracks and providing connective issue. Sometimes, this form of Telling will need to be a placeholder for something that is Shown in a later draft, but often times, that throwaway line or brief exchange of expositional dialogue that you throw into a random scene is more than enough to tie the things you’ve already Shown and Told together.

Which brings me to the example that inspired this post.

Incomplete Runes

At the time of writing this, I’ve just finished Runebreaker, an indie Romantasy novel by Mila Finch. I plan to review this book sometime in spring (depending on when it will fit into the schedule). It’s … not going to be a positive review. The author had a couple of good ideas that hooked me early on, but it very quickly dissolved into a bog-standard female power fantasy where the “romance” is just pornography.

After I realized exactly what sort of Romantasy I’d picked up, I was prepared to soldier through it and try to give a positive (or, at least, middling) review for its narrative qualities outside of the cliché and sludge. The problem was that there is a pervasive issue that undermines everything else in the story. When we do the review, I’m going to refer to this problem as “the author’s assumption”, a term I heard KrimsonRogue use in his review of Lightlark.

Finch threw a lot of elements into this book that seem contradictory. Some of them are contradictory (and believe me, we will be getting to that), but for others, it’s not impossible to imagine how they could tie together in a consistent manner. The issue is that this explanation is not in the narrative. Maybe these ideas made sense in Finch’s head, but she didn’t give us enough on the page to see things the way she did. It’s like she assumed we’d all just be on the same page at her.

To take just one example, let’s consider the lore about the setting’s dragons.

Early in the book, it’s established that dragons are extinct for “over a thousand years”. Their bones and blood are established as magical ingredients, but they’ve been dead so long that anyone who claims to possess either ingredient is either lying or gullible. (Later we are told it has been “two thousand years.”)

Shortly after this, Bad Boy Love Interest procures gloves made of dragon hide for Main Character. These are explicitly gloves that he had “made” for her. How, exactly, did he have dragon hide available? The fact the blood and bone is all gone implies that dragon tissues were extremely rare ingredients and/or decay like any other organic matter, so it seems unlikely that he just happened to have workable hide available unless it was harvested from a dragon more recently.

Later, when Main Character jumps at a shadow, thinking it a dragon, she chides herself for it in the narration by saying: “Dragons were legends that [Nice Guy Love Interest] had rambled about, nothing more than a story to tell children.” So were dragons real or not? Is the legend that dragons still exist when they are, in fact, all gone?

After that, we get the reveal that dragons used to rule the world before the fae overthrew and imprisoned them. Not only this, but the dragons bred with fae (and, at least indirectly, with humans) to produce hybrids capable of administering their civilization. I can understand the fae suppressing this information to avoid looking vulnerable in front of the humans they now rule over, but shouldn’t that affect how they talk about dragon legends and dragon ingredients among themselves (or when around a human they trust, like main Character)? Shouldn’t that affect their record-keeping regarding seals to keep the dragons imprisoned? To make things even more confusing, one these seals requires annual maintenance, and yet everyone has apparently forgotten where it is while actively performing the annual maintenance on it.

Further adding to all of this confusion are the ambiguously long life spans of fae. Bad Boy Love Interest himself explicitly states that he has “over a thousand years”, and there are fae older than him. The imprisonment of the dragons should still be in living memory, or at most, no more than a generation or two in the past. How is there not clear information available about the dragons in-world?

It would not have been hard to clarify this with Telling. For example, prior the discussion of fake dragon bone, there is a passing mention of dragon blood, and Main Character fleetingly wonders, “Who had access to that?” before turning her attention elsewhere. By Telling us more to go with that question, Finch could have resolved at some of the contradictions. For example, she could have done something like this:

Who had access to that? Dragons vanished long ago. Now, the only things left of them were pieces of their hide, which remained impervious to the passage of time, and stories used to frighten children and justify the Rite.

And this isn’t the only example of easily resolved contradictions in the book. Telling could have made the things we’re Shown link together in a logical manner. The gaps we are left with instead makes it hard to engage with the material in any way except knee-jerk emotions with no thought behind them.

Showing could also have worked to resolved these issues, of course. It’s just that doing so would have taken more time. To preserve the book’s pacing, other content would likely need to have been cut to balance things out. Something would have ended up being Told either way.

SHARING IS CARING

The ultimate objective in balancing Show vs. Tell is to optimize the audience experience. The reason Show Don’t Tell is emphasized is that Showing maximizes the impact of the information. Elements are more emotional, more memorable, and generally carry more weight when demonstrated to the audience. However, Telling is vital for narrative efficiency. To keep bloat down and the pacing up - and, for that matter, to emphasize the more important elements of the story via contrast - it is sometimes necessary to just exposit things to the audience and keep things moving forward.

There’s nothing wrong with the adage of Show Don't Tell. It’s just important to remember that it is a hammer. Not every narrative problem is a nail.

Thank you all for joining me today. Please subscribe and share if you enjoyed what you read here. Take care, everyone, and have a good week.

In two days, Volume I of my first serialized Romantasy novel, A Chime for These Hallowed Bones, premieres!

Kabarāhira is a city of necromancers, and among these necromancers, none are more honorable or respected than Master Japjot Baig. Yadleen has worked under him since she was a girl, learning how commune with bhūtas and how to bind these ancient spirits into wights. Her orderly world is disrupted, however, when a stranger appears with the skeleton of a dishonored woman, demanding that her master fabricate a wight for him.

To protect her master from scandal, Yadleen must take it upon herself to meet this stranger’s demands. Manipulating the dead is within her power, but can honor survive in the face of a man who has none?

You can see the full schedule for Volume I here! I hope you’ll join me on this new adventure.