The Will of the Many (Part 1 - Overview & Prose)

Hello, all. Welcome to our first 10/10 review.

The Will of the Many wasn't a book that I intended to write a review for. I actually had very little interest in reading it at all. I liked what James Islington did with the Licanius Trilogy, but after the way that The Light of All that Falls stumbled at the finish line, I didn’t want to read any new projects by him until he delivered on his promise to release a book covering the chapters he cut from that finale.

However, in May, I was experiencing some burnout. I needed a break from my usual review fare to read something purely for my own enjoyment. Despite my frustration with The Light of All That Falls, I still enjoyed Islington’s work, so I gave in and picked up The Will of the Many.

And … wow. I was blown away.

The Will of the Many isn’t just a spectacularly crafted work of Fantasy. It takes so many of the things I have critcized and complained about in The Empyrean (and other recent Fantasy, too) and does them right.

It lacks subtlety, yet in a manner that respects the audience and makes sense for the story being told.

It tells a Magic School narrative without the school drama bogging down the narrative.

It juggles a massive cast of characters without them dissolving into a Red Shirt mob or accessories for the protagonist.

It has a highly skilled and intelligent main character who not only demonstrates these abilities in a believable way (i.e. without everyone else around him being dragged down to make him look better by comparison) but is also challenged and tested and given chances to grow at every turn.

It employs a Soft Magic system without said magic system becoming a crutch to force the plot in random directions.

It features a Romance subplot that not only feels genuine, with substance it beyond sex, but also introduces conflict into that dynamic in a natural way.

The Will of the Many needs to be analyzed in depth. It’s not enough to just say that it is great and that people should read it (though more on that particular thought in a moment). We need to take time to really get into all the examples that can improve us as writers, especially those of us who are writing Fantasy. I’ve got too much on my plate right now to dissect it in book club-style review (though it would certainly be possible to do that - the writing really is that high-quality), but the least we can do is a brief series to hit the highlights.

STATS

Title: The Will of the Many

Series: Hierarchy (Book 1)

Author(s): James Islington

Genre: Fantasy (Epic)

First Printing: May 2023

Publisher: Saga Press (imprint of Simon & Schuster)

SPOILER WARNING

Minor, unmarked spoilers for The Will of the Many will be provided throughout this review. I will keep the first paragraph of each section as spoiler-free as possible. Heavy spoilers will be confined to clearly labeled sections.

No spoilers will be provided for the sequel, The Strength of the Few. That book is not yet released as of the time of this post (though it will be by the time this review series concludes), and I have not read any of the available sample chapters.

Spoilers may be provided for other works of fiction as necessary to support the analysis. If a work is less than 10 years old, I will try to avoid heavy spoilers or else clearly mark them, but for works older than that, I’m not going to be providing any warning unless I feel that the spoiler in question would fundamentally impact the experience of consuming that story for the first time.

STRUCTURE

This review will be split into four parts, releasing biweekly over the next month and a half.

Part 1 (this part) - An overview of the various odds and ends that normally get included in one-shot reviews, along with a discussion of the prose

Part 2 (October 17th) - A discussion of the worldbuilding, including the successful implementation of the Soft Magic system, and themes

Part 3 (October 31st) - A discussion of characters including the handling of the overpowered Main Character, the execution of the Romance subplot, and the juggling of a large cast of named characters

Part 4 (November 14th) - A discussion of the plot, including the incorporation of the Magical School elements the setup / payoff of twists, and how it functions as an entry within a series

The Strength of the Few releases on November 11th, so we’ll be concluding this review at the perfect time for you to pick up a copy of the sequel for yourself (though I do recommend reading The Will of the Many for yourself, as there is a lot of important details that I simply can’t capture in a review of this length).

TERMINOLOGY

The title of this book s a mouthful, so we’ll be abbreviating it from The Will of the Many to Many. I considered going with just Will, but because Will is a critical element of the magic system, I wanted to avoid the confusion of needing to discuss Will and Will alongside each other.

PREMISE

I read Many as a Kindle e-book, so let's see what Amazon has to say:

The Catenan Republic—the Hierarchy—may rule the world now, but they do not know everything.

I tell them my name is Vis Telimus. I tell them I was orphaned after a tragic accident three years ago, and that good fortune alone has led to my acceptance into their most prestigious school. I tell them that once I graduate, I will gladly join the rest of civilized society in allowing my strength, my drive, and my focus—what they call Will—to be leeched away and added to the power of those above me, as millions already do. As all must eventually do.

I tell them that I belong, and they believe me.

But the truth is that I have been sent to the Academy to find answers. To solve a murder. To search for an ancient weapon. To uncover secrets that may tear the Republic apart.

And that I will never, ever cede my Will to the empire that executed my family.

To survive though, I will still have to rise through the Academy’s ranks. I will have to smile, and make friends, and pretend to be one of them, and win. Because if I cannot, then those who want to control me, who know my real name, will no longer have any use for me.

And if the Hierarchy finds out who I truly am, they will kill me.

Reaction

This premise wildly oversells the school element of the story.

Don’t get me wrong - the Academy is incredibly important to this story. That whole bit about finding answers is indeed the task Vis needs to complete at the Academy. At least half of the book takes place at this location.

However, this premise makes it sound like this is a Magic School story. It really isn’t. If anything, it’s a Cerebral Thriller story wrapped in Epic Fantasy, with the Magic School serving as set dressing. Vis doesn't even get to the school until a third of the way through the plot, and once he’s there, the story only engages with the school for political ladder-climbing.

What I suspect happened here is that the publisher is trying to cash in on the craze for The Empyrean. This premise sounds awfully similar to what might be written on the back on Fourth Wing or Iron Flame. Magical schools and assorting training academies are coming back (or being pushed back) into vogue, so the publisher put focus on that.

RATING: 10 / 10

This is a phenomenal Fantasy text that rights so many wrongs I have seen in stories like it. That being said, I need to present this rating with a caveat.

I do my best to present these ratings as something separate from subjective experience. You’ve probably noticed that, in a handful of my past reviews, I’ve given good ratings to books I didn’t much enjoy reading, while giving a below-average rating to at least one book that I did. My subjective enjoyment of a book is influenced by objective quality to some degree, but these two values aren’t meant to be the same thing.

Many is a case of a book that I firmly believe is objectively good. It’s flaws so superficial that they don’t hurt the overall quality. I did consider putting it at just a 9.5/10, the way I did for Jade City a couple of years ago. However, the reason that Jade City lost out on a 10/10 came down to the back third feeling like it was missing a couple of chapters, a fact that undermined the climax. Many doesn’t have that problem.

So, this is a great book. I loved it … but that doesn’t necessarily mean that you will.

This book is dense. The prose is dense. The lore is dense. While it is well-paced and does have rising and falling tension, the tension spikes very high. All this is to say that this book can be tiring to read at times. Couple that with length, and this is book is almost the inverse of Paolini’s highly accessible Fantasy.

This is a book written for very hardcore Fantasy fans or people who love deeply thematic storytelling. I highly recommend it if you fall into either of those categories. If you don’t fall into those categories, I want to give fair warning that this book may be a bit of a challenge for you.

CONTENT WARNING

Many features a great deal of violence. Most of this takes the form of small, personal fights between Vis and one or two other opponents, but we do also get a terrorist attack that kills thousands of civilians. While it does get brutal at times, I don’t think it’s overdone. It never feels like violence is being rammed in for violence’s sake. Even the violent scenes with the least relevance to the plot are extensions of character and have consequences that ripple forward through the story.

That said, there is a lot of gore. It’s not WH40K levels, but Islington does not shy away from gruesome descriptions, whether those be of a body that has been brutally hacked by blades or multiple people liquefied by a shockwave. Again, it’s not overdone, only being used to the extent necessary to convey the tone or tension that Islington is going for. It’s also not a crutch. Islington could have omitted the gore and gotten the same results; by including the gore, he merely amplifies what was already on the page.

Torture surfaces indirectly throughout this story. We’re Shown scars on Vis’s body and Told that he has endured multiple whippings for refusing to cede his Will. There are also devices called Sappers, which are introduced in the first capture. These are tools of torture that the Hierarchy uses in the place of capital punishment, trapping people in a state of full-body paralysis while the maximum possible amount of Will is continuously drained from them.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIALS

Much like The Empyrean, Murtaugh, and The City of Brass, Many has supplementary materials for the reader. I feel like the execution of these materials enriches the story for readers who care about them rather than assigning homework (as was the case in The City of Brass) or creating more confusion than they address (as has been the case for The Empyrean). Much like Paolini did in Murtaugh, Islington keep the information to what was most helpful to the audience.

Preface

Dedication

Unlike with the dedications for The Empyrean, Islington doesn’t give me anything to really analyze, other than perhaps hinting as some emotional baggage that may have motivated him to write certain characters in plot elements in specific ways.

For friends, lost.

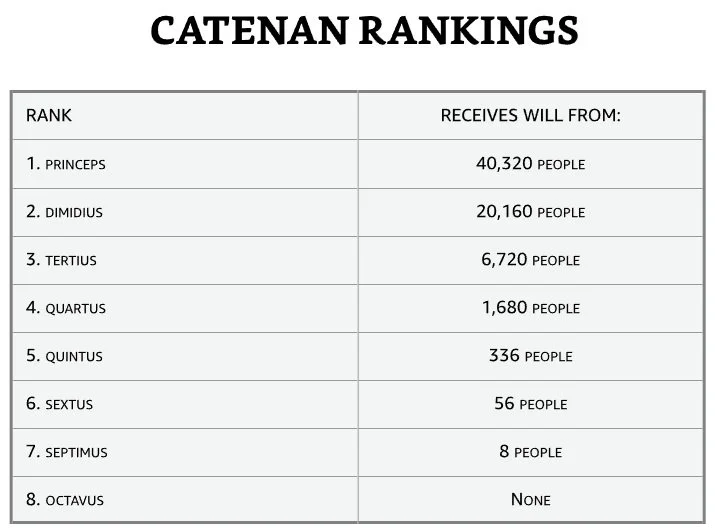

Catenan Rankings

The name of the Catenan government (and this book series), the Hierarchy, isn’t just an SAT word slapped onto the text for evocative value. The hierarchal structure that exists within the setting is essential to plot progression, character motivations, and worldbuilding. Where an individual exists within this hierarchy affects not only political status but also their power within the magic system. We’ll get into this properly in Part 2. For now, I’ll just show you the table that Islington provides before the story proper begins.

I feel like this is an effective inclusion. This isn’t homework. You don’t need to understand precise numbers of how many people cede will to a person on any given level of this power structure. Still, if someone does want to wrap their head around precisely how many people this adds up to, the information is readily available.

To be extra sure I had nothing to criticize here, I also checked Islington’s math. For every rank higher than Septimus, the number of people from whom someone of that rank receives Will is reflected by the function F(A,B) = (A + 1) x B, where:

A is the number of “Rank”

B is the value of “Receives Will From” for the Rank below A

How this actually plays out in the lore is a bit more complicated than this, but again, that’s something we’ll get into with Part 2.

Postface

There are five things tucked back here:

Acknowledgements

Major Characters

Glossary

Locations

About the Author

The first and last items on this list are standard fare for fiction and don’t reveal anything critical to understanding the narrative. The remaining three serve as catalogs of pronunciations and descriptions / definitions to help readers keep track of names and terms being tossed around in the narrative. They’re good as reference documents but aren’t required reading.

PROSE

Voice & Immersion

After reading The Empyrean, where the narrative voice is at odds with the setting and thus spoils immersion, I found the prose in this book to be incredibly refreshing. This work of Epic Fantasy reads like a work of Epic Fantasy - that is to say, every aspect of the prose aligns with the story being told. We’re not being promised a sweeping romance in the midst of a grimdark war drama, only to be presented with the ramblings of a modern American university student who clearly knows no world beyond the luxry of the modern US. We are experiencing a tale of danger and intrigue through the eyes of a character who lives within this world.

1st Person POV

The advantage of 1st Person POV is that it puts the reader inside the head of the narrator. This is damaging in The Empyrean because (A) Violet doesn’t conduct herself like a character who lives within this world and (B) Yarros has zero filter when it comes to sharing Violet’s impulses with us. This creates a powerful dissonance. It’s hard to fully experience the events of this story when our viewpoint onto the world feels like she’s a visitor herself, and it’s hard to want to get invested in the story when the viewpoint character is so repulsive.

In Many, both issues are addressed. Vis does feel like a character who is part of this world. He approaches problems as someone who dwells within this world, thinking in terms of the morality and philosophy that his background would have exposed him to and possessing values consistent with his experiences. As for likeability, while Vis is a flawed individual, Islington practices moderation with his impulses. We’re not being asked to empathize with him while he obsesses over sex and yearns for the death of anyone who mildly inconveniences him.

This allows the advantages of 1st Person POV to really shine. The narrative is rich with Vis’s own voice, and his emotions in any given situation flow off the page.

Present Tense POV

This may surprise those of you who read “The Unbottled Idol”, but prior to reading Many, I had a very dim view of Present Tense POV. I knew that there was a time and a place where it can shine, where it could lend a sense of urgency to the flow of events (especially for scenarios where the POV’s survival is in question), but I personally had few good experiences with it. I mainly saw it as a gimmick applied by amateur writers.

The Empyrean has offered nothing to disabuse me of this notion. Even ignoring the fact that Present Tense clashes with the framing device (that the series is a translated selection of historical accounts), Yarros consistently fails to construct scenarios were the tension is believable. The use of Present Tense is the only think going for her, and because Violet is a Mary Sue, even that isn’t enough to prop up the story.

Many completely changed my perspective. This is the perfect story for Present Tense. Vis is constantly being tested by either physical or social challenges. There is a genuine risk of his death - or, worse, imprisonment in a Sapper - if he cannot achieve his goals. Once it becomes clear that Vis is the only POV character, we understand that he will need to survive until the end of the story, but Islington has work-arounds for this, giving Vis chances to redeem himself as the threat of the Sappers looms larger or else putting Vis in scenarios where we’re eager to see just how he’ll get out of trouble.

For example, near the halfway point of the book, Vis is put in a scenario where he can either succeed in a task or drown. He’s obviously not going to drown. This should kill the tension, except at the last second, Islington introduces a wrinkle that triggers a moment of genuine panic for Vis. While this only lasts for a couple of pages, it does serve as a flash of believable tension. While Vis does survive, he also suffers consequences for his mistake, thereby providing a sort of payoff to the tension.

All this is to say that this story builds a believable sense of urgency before Present Tense is applied. This isn’t a gimmick or a crutch. Islington is enhancing something that he’s already achieved.

Language, Density & Voice

These two are somewhat intertwined, so we might as well mesh them together.

As you might have picked up from that Catenan Rankings table, the Catenan Republic draws a lot of influences from the Roman Republic. This includes the heavy use of Latin in the text. This is never so dense as to make it impossible to understand what happening, but it does mean that there are a lot of names in this book that are real mouthfuls. (Also, while not related to the narrative itself, all the chapters are numbered with Roman numerals, which might make it harder for some people to look things up or find their place in the narrative.)

This use of Latin contributes to the sense of density. This is not a light read. Every line of dialogue and every line of narration (which, given that we are in 1st Person Present POV, is effectively Vis’s internal monologue) reads like it was written for a person who dwells in this world where the primary language is Latin (or a Fantasy analog), a world that also doesn’t share our modern conveniences, sensibilities, and lifestyles. On top of that, Vis is a very intelligent character who is constantly assessing every angle of his interactions with other characters, meaning that scenes that might otherwise be simple are dissected to an exhausting degree.

What I’m getting at here is that, while Many is a very enriching read, it is also a tiring one. This isn’t a book you casually pick up and breeze through in a few hours. If you’re a long-time fan of Epic Fantasy, this may not bother you, but if you’re expecting the excessively modernized prose of The Empyrean or the accessibility of Paolini’s work, this book may be extremely challenging for you.

Subtlety

In past reviews, I’ve complained about writers insulting the intelligence of their audience through a lack of subtlety. Things that were conveyed effectively through implication then get spelled out to the audience, thereby ripping away the emotional impact of the implication and denying the audience the satisfaction of picking up on key details for themselves. While spelling things out for an audience is something that certainly can be done, it needs to be done in moderation and justified within the text itself.

Many is a very unsubtle book. Through Vis’s POV, we have our hands held through every interaction. Every implication and every nuance of body language is explained to us. This becomes particularly obvious in Chapter V, when we first see Vis’s talents for deception and verbal manipulation being put to the test. There are multiple examples I could pull from this conversation, so I grabbed one at random. Note all the points where we’re told something that is either implied or better off just being Shown (marked in bold).

“A man’s face is different when he’s hearing and when he’s listening. Something about the eyes.” Ulciscor shrugs. “If it’s any comfort, I almost missed it.”

It’s not.

There’s silence as I struggle with the situation. Maybe all of this is just about what I overheard.

“I didn’t really catch much of what you said to the prisoner. And I barely understood what I did.”

“Any of it is too much.” There’s implied menace in Ulciscor’s gentle smile. “But I think there may be a way we can work this out, to both our benefits. So let’s start again. Without the lies, this time.”

“Alright,” I lie.

“Good. Now. Let’s start with the Sapper. I saw you touch it last night. Don’t deny it,” warns Ulciscor, stilling any protest I might have made. “Do you know why you weren’t affected?”

There’s too much confidence across the table for repudiations. “No.”

Ulciscor nods, approving my lack of dissembling. “I have a theory, but first I need you to cede some Will to me. Just a little.”

One or two of these might not be an issue, but this brief passage has five, and the entire conversation is like this. The audience isn’t being allowed to draw our own conclusions. Vis is doing all the thinking for us.

… but that’s the point.

While Vis has multiple skills that are put to the test in this story, his most important one is his ability to navigate a conversation. It’s a skill he honed over three years of keeping his identity secret while also avoiding situations where he’d need to cede Will. This demands that he not only know how to lie convincingly but also be able to read people so as to know what lies to tell and when.

Islington isn’t spelling everything out because he has zero faith in our ability to understand what’s happening. He’s spelling it out so that we can experience the world as Vis does. The provided detail helps us to understand what it’s like for Vis to tiptoe around the truth when one wrong word could get him killed or condemned to a sapper. This is a prime example of a situation where less subtlety actively benefits the narrative.

A WORLD OF HIERARCHIES

On October 3rd, we’ll dive into Part 2 of this review, where we’ll explore Worldbuilding and Themes.

Much like with the Licanius Trilogy, Islington has fabricated a world that carries an immense sense of both depth and history. A few ideas have been recycled, most noticeably the trope of a fallen Precursor Civilization and the use of a magic system built around the manifestation of an abstract concept. However, whereas the world of the Licanius Trilogy didn’t have obvious real-world influences (that I could recognize, at least), here Islington leans deep into Roman history to create a world that is far more familiar while also being built around its own unique history and circumstances.

Those of you who read the Licanius Trilogy will not be surprised to learn that Islington also leans deep into thematic worldbuilding. The magic system of this world doesn’t exist separately from the big ideas of the narrative. Without Will, the thematic ideas of this story either wouldn’t exist or couldn’t be explored to quite the same depth. This entire world feels like it is structured to deliver a rhetorical argument, and it does so without every feeling artificial.

There are more great lessons for us to learn. I hope you’ll join me for them.

HOUSEKEEPING

Scale of the Problem

Speaking of worldbuilding, the analysis of Chapter 44 of Onyx Storm, releasing next week on October 10th, is going to be a discussion of scale.

A book doesn’t need hard numbers for things like populations, travel times, distances, or army sizes to be a good story. Authors make mistakes. Most of the time, these mistakes are small enough that they’ll only be noticed by subject matter experts or people who are passionate about figuring out how fictional settings work

Onyx Storm is a very different beast. At a couple points in this book, Yarros has given hard numbers that clash so violently that something felt off on a first read. Actually thinking about these numbers made things so much worse. While it wouldn’t be impossible to tell a Fantasy narrative where all these numbers are true, Yarros has not put in the legwork to allow them to coexist harmoniously. And, since one of those clashing numbers is here in Chapter 44, now’s a good a time as ever for a Spotlight analysis on the topic.

Farewell

Whatever you’re here for, thanks for stopping by this week. Please remember to subscribe to the newsletter if you’d like weekly e-mails with the latest post links. Please also share this review with others if you enjoyed it. Take care, everyone, and I hope to see you again soon.